The dreams of the Grenada Revolution were crushed in October 1983 by a quick succession of dramatic coups, starting with a power struggle between competing factions of the People’s Revolutionary Government. Maurice Bishop, the popular leader of the 1979 socialist revolution and subsequent Prime Minister, was first placed under house arrest, after a takeover by his deputy, Bernard Coard. But Coard only ruled for three days, before he himself was deposed by the army led by General Hudson Austin, who executed Bishop and other leading politicians. A week after Bishop’s murder, the United States unleashed Operation Urgent Fury to remove Austin’s military junta. The decision by US President Reagan to invade Grenada was unpopular with many of his allies at the time and remains controversial.

Espionart has previously told how a comic book produced by the CIA was airdropped over the Caribbean island during the invasion, portraying the US army as liberators. Others continue to claim that Operation Urgent Fury was instead a calculated move to strengthen US influence in the region after several neighbouring countries had fallen into the Soviet sphere. In just three days, an American victory heralded the establishment of a conservative government with a strong alliance to the US, marking the end of Grenada’s revolutionary years.

The new government began to wipe out the memory and artistic traces of the ‘Revo’, as the 1979 revolution to end the authoritarian rule of Eric Gairy was known locally. In the summer before the overthrow of Bishop’s government, American university professor Betty LaDuke visited Grenada to assess the impact of the revolution. Her enthusiastic paper, Women, Art, and Culture in the New Grenada (available through JSTOR), paints a picture of an island full of hope, promise and creativity. LaDuke describes “strikingly beautiful” wall graffiti, murals and posters dotted around both town and countryside: “Throughout the country the manifestation of Grenadian solidarity with Prime Minister Maurice Bishop’s government is visible in the spontaneous paintings on brick and rock walls and sides of houses.”

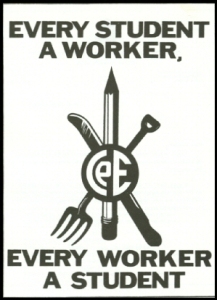

Also evident were brightly-coloured billboards, the results of a state-funded artistic project. In a speech of late 1980, Bishop had declared that “Education is a Must!” At the same time, the Center for Popular Education (CPE) was launched, sending over a thousand volunteer tutors to mainland Grenada and the Grenadine Islands to teach the largely-illiterate adult population to read. To support this literacy movement, the government sponsored artist Gordon Hamilton to lead a team of designers and painters in producing billboards, encouraging the population to pursue the collective goal of self-betterment.

Also evident were brightly-coloured billboards, the results of a state-funded artistic project. In a speech of late 1980, Bishop had declared that “Education is a Must!” At the same time, the Center for Popular Education (CPE) was launched, sending over a thousand volunteer tutors to mainland Grenada and the Grenadine Islands to teach the largely-illiterate adult population to read. To support this literacy movement, the government sponsored artist Gordon Hamilton to lead a team of designers and painters in producing billboards, encouraging the population to pursue the collective goal of self-betterment.

Many billboards bore popular revolutionary slogans such as “Forward ever, backward never!”, as well as motivational statements expressing the new government’s egalitarian spirit: “Never Too Old to Learn”, “Education is Production Too”, “Every Worker a Learner”, “Women, Committed to Economic Construction”, and more. The CPE billboards were constructed from galvanised sheeting and decorated with oil-based house paint, with up to thirty a year placed in strategic positions among rural communities.

Grenada’s CPE billboards mirrored the contemporaneous revolutionary murals of neighbouring Nicaragua – which would likewise be later destroyed in a wave of political iconoclasm – as well as the murals and posters produced in support of radical political movements, from the Soviet Union and Cuba to Ethiopia and the United States.

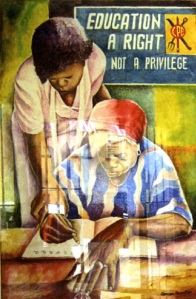

Despite this, Hamilton did not consider the billboards to be artworks, and they were neither signed nor photographed to document for posterity. Today, only a handful of amateur photographs exist to record this vibrant moment of public art in Grenada, before the billboards were painted over or reclaimed as housing materials. However, as part of the 2011 exhibition Grenada 1979–1983, Revolution: An Art Perspective, held in the Grenadian capital of St George’s, Hamilton recreated in watercolour one of his revolutionary billboards, this time proudly displayed as a work of art.

Despite this, Hamilton did not consider the billboards to be artworks, and they were neither signed nor photographed to document for posterity. Today, only a handful of amateur photographs exist to record this vibrant moment of public art in Grenada, before the billboards were painted over or reclaimed as housing materials. However, as part of the 2011 exhibition Grenada 1979–1983, Revolution: An Art Perspective, held in the Grenadian capital of St George’s, Hamilton recreated in watercolour one of his revolutionary billboards, this time proudly displayed as a work of art.

The 2011 exhibition was unpopular with many Grenadians, who were keen to avoid stirring up bad memories. As local artist and the exhibition’s curator, Suelin Low Chew Tung, recalls in her essay Painting the Grenada Revolution (also available through JSTOR), “images of the revolution years were deliberately erased from the landscape … Three decades later, as far as local visual art records are concerned, it is as if the Grenada Revolution never happened.”

LIKE THIS STORY?

Here are some other Espionart posts you might enjoy:

One thought on “The Billboard Art of Revolutionary Grenada”