On 7 January 1979, the Vietnamese Army invaded Cambodia – sweeping from power the brutal regime of the Khmer Rouge. While both were ostensibly Communist states, relations between these neighbours had dramatically deteriorated due to the stream of Cambodian refugees into Vietnam and the Khmer Rouge’s repeated forays into border towns, where residents were massacred. The Vietnamese occupation would last for another ten years. Yet despite the revelations about the Cambodian Genocide, in the aftermath of the Vietnam War the newly-formed Socialist Republic of Vietnam was so reviled by many regional neighbours and Western countries that they preferred to support the Khmer Rouge’s attempts to reclaim rule. However, when Pol Pot and his supporters were partly restored to power in 1989, in a coalition brokered by the United Nations, they reneged on their agreement to participate in elections and instead returned to their insurgent roots, killing ethnic Vietnamese citizens and attacking UN peacekeepers.

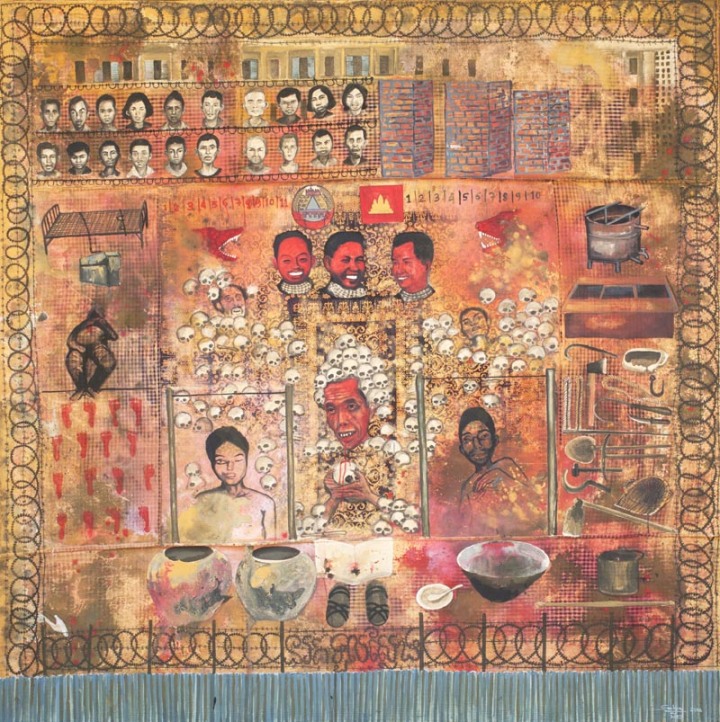

Espionart has previously explored the struggles of Cambodia’s few surviving artists to recover from the Khmer Rouge’s four-year rule, during which time up to a quarter of the country’s population was killed in forced labour camps. A special feature also focused on the horrific experiences of painter Vann Nath, imprisoned along with fellow artist Bou Meng. During their incarceration, the artists were forced to create glorifying images of the regime while witnessing the daily torture and execution of fellow inmates. Born in the early 1970s, Leang Seckon was only a small boy while his fellow artists lived through that ordeal. Yet forty years later, his mixed-media collage Hell of Tuol Sleng recorded events in the notorious prison where they were held, as part of the series Hell on Earth.

Growing up on the Cambodia-Vietnam border, Leang Seckon was a witness to war in his earliest years. Believing that the area was a hideout for the Viet Cong, the US began to carpet bomb the countryside from the late 1960s, followed by ground offensives by South Vietnamese forces. Today, Leang is one of Cambodia’s most well-known artists, but the dark days of his childhood continue to haunt his work. Having trained at the Royal University of Fine Arts in Phnom Penh, he has gone on to see his work exhibited internationally at biennales and art fairs, and in dedicated exhibitions in London, Hong Kong, Singapore and New York.

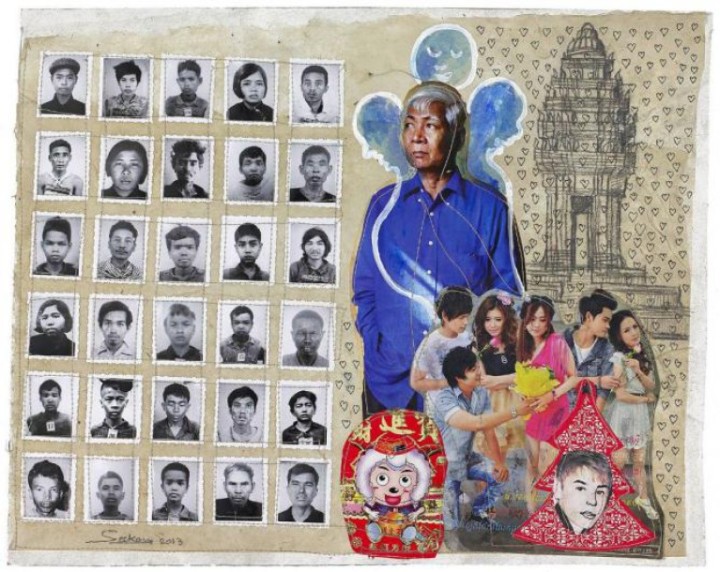

Leang’s favoured style is collage, dense webs of detail combined in paintings or thickly embroidered tapestries, filled with human faces and decorative elements. Into these he often incorporates found objects that refer to the country’s lost heritage, subverting the colourful and enticing surface with ominous or violent swirls of content. Blending Surrealist visions from local legend with personal biography and pop culture, Leang pays homage to the vibrancy of Cambodian visual culture as well as the country’s harrowing history.

In Parasol of the Moon, a twinkling night sky, reminiscent of Van Gogh’s Starry Night, is transformed upon closer inspection into a portent of impending danger. The decorative stars are revealed to be parachutes falling to the ground, providing targets for aerial bombing campaigns. As the artist has recalled, “In the early 1970s, the Mekong River formed a border between the Communist occupied areas and free American supported areas. The city of Phnom Penh, filled with dancing, singing, concerts and fireworks, was soon to be hit by grenades and bombs”.

Many of Leang’s works have religious overtones, a reclaiming of Cambodian culture after the Khmer Rouge attempted to stamp out Buddhism. Indeed, the resurgence of religion since the 1970s has provided some solace for Cambodians, who have traced earlier events to a prophetic nineteenth-century Buddhist text called the Buddh Damnay. Predicting that “war will break out on all sides…blood will flow up to the bellies of elephants; there will be houses with no people in them, roads upon which no-one travels; there will be rice but nothing to eat,” the text explains the suffering as marking the mid-point in a cycle between two buddhas, with a better future assured by the coming of the next Buddha.

Leang’s style also extends into sculptures and installations, often formed from the remnants of buildings used by the Khmer Rouge to commit their atrocities. In another series, skeletons are adorned with embroidered textiles mixed with military paraphernalia left behind by wars and foreign invasion, such as French rifles, US Army helmets and Khmer Rouge shoes made from tyres. These installations have also been used in performances staged by the artist. At a gallery in London, he relived his childhood trauma as a baby, emerging from the skirts of his mother. In another, Buddhist monks, Vietnam War veterans and genocide survivors joined the artist in parading his Flowering Parachute Skirt across the campus of Columbia University in New York. The skirt was created from a Vietnam War parachute recovered from his home village, onto which flowers were stitched by Cambodian women, who shared their experiences while they worked.

Leang’s collages, paintings, sculptures and video work also deal with the challenges of Cambodian life after the Killing Fields, as the pressures of modernisation and industrialisation threaten both individuals and the environment. “People that survived the war have been thrown into this rapidly developing society, which has made them move forward too quickly,” explains the artist. “They have not had the time to reflect on contemporary life and society in relation to their past. As a result, everything seems unclear, confused and of low quality”.

While Leang Seckon’s work has proved popular, there are some who resent ongoing references to the Khmer Rouge’s genocidal behaviour in the work of contemporary Cambodian artists. One artist’s attempt at catharsis, to ease collective trauma, can be seen by others as an exploitation of that suffering while playing to an international audience.

All images: Leang Seckon © The artist and Rossi & Rossi.

LIKE THIS STORY?

Here are some other Espionart posts you might enjoy: